Bison Bridge More Than Half Way Toward Public Support Goal

One month after Quad-Cities environmentalist Chad Pregracke announced his ambitious Bison Bridge plans, the creative concept has earned over 27,000 supporters online, an endorsement from The Chicago Tribune editorial board, and a strong social-media shoutout from TV’s Mike Rowe.

Chad Pregracke, founder of Living Lands & Waters.

“This is VERY cool. My old friend Chad Pregracke – whom many of you will remember as the self-appointed garbageman of America’s rivers – is on a mission to create a brand new National Park on the Mississippi River,” Rowe (well-known for cable’s “Dirty Jobs”) posted on Facebook late last month of plans to preserve the old I-80 bridge and repurpose it into something “utterly unique – a Bison Bridge.”

Chad isn’t looking for money or volunteers, Rowe wrote – “he’s looking for signatures from people who think a Bison Bridge is a perfect way to celebrate the prairie, the wildlife, the Mississippi, and the history of the area.

“It’s not a tax funded thing, but he’s got to convince the powers that be to get on board with permits and permissions and so forth. Give it a look, and if you think it’s worthwhile, leave your name behind,” he said, attaching the video for the project. “Then, years from now, you can tell your kids you helped build the most unique national park in the country, and the only Bison Bridge in the world…”

As of the first week of April, the Bison Bridge Foundation had attracted well over 27,000 online supporters (toward a 50,000 signature goal)

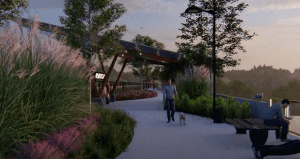

The planned Bison Bridge would include a visitor center.

for the multi-purpose plan.

The support page of its site says: “You will receive a periodic newsletter with status updates, project developments, and pertinent information regarding our efforts. You will not be solicited for donations. Join the herd by completing the form below.”

Pregracke’s long-term vision (unveiled to the public March 18) is to turn the Bison Bridge and the acreage on either side of the Mississippi River adjacent to the bridge into a new National Park. Visitors will have the chance to learn about the history of the prairie, native wildlife, and the historical significance of the river.

With over 42,000 cars a day traveling over the Mississippi on I-80, the Bison Bridge will attract locals and visitors alike for the chance to experience all the river and the region have to offer, according to project supporters.

Completed in 1966, the four-lane Fred Schwengel Memorial Bridge connects the Q-C between LeClaire, Iowa, and Rapids City, Ill. In 2020,

The current I-80 bridge over the Mississippi may be demolished after construction of a planned new bridge.

the Illinois Department of Transportation began a preliminary study to replace the bridge. (The bridge was renamed in 1995 in honor of the former Iowa Congressman.)

After forming Living Lands & Waters in 1998, Pregracke has had this bridge idea for 20 years, to make this an iconic attraction for the region. LL&W has been working on prairie restoration next to the bridge on the Illinois side.

The project comes as the Illinois DOT is studying the future of the 55-year-old infrastructure and preparing to make decisions about the location and design of a new I-80 replacement bridge. Bison Bridge plans to have the current westbound lanes as a forested, vegetation-filled bison refuge – the largest wildlife crossing in the world — and the other side as a pedestrian-bike crossing, with many amenities.

“It’s a fantastic idea, a heck of a vision,” Kevin Marchek, who worked over 39 years for IDOT, said last month. “We’ve just got to keeping pushing this until it comes to fruition.”

Bison Bridge has the potential to save the state millions of dollars in demolition costs. “That’ll be a huge benefit to the state too,” he said. The three-phase process for a new I-80 bridge will be looking at environmental impacts, designs and plans, and the last phase is construction, which would take seven years before building, Marchek said.

“Time really flies when you start working on a project like this,” he said. “We’re right at the perfect spot now, at the beginning.”

A Chicago Tribune April 7 editorial called the idea “startling” but “too charming and creative to reject out of hand.”

It noted that Pregracke and his allies see Bison Bridge as a way to get some of those drivers who cross the bridge to “stop and discover what this sizable metropolitan area has to offer.”

The nighttime vision for the proposed Bison Bridge.

“Ah, but would it be good for the bison?” the editorial asked. Jason Baldes, tribal buffalo manager for the National Wildlife Federation’s Tribal Partnerships Program, helped place a small herd at Wyoming’s Wind River Indian Reservation and said he is “very proud to be part of the project.”

“We’d wager that lots of people would get a kick out of seeing wild bison going about their business,” the Tribune said. “And who knows? Maybe the bison, meandering high above the mighty Mississippi, would love the view.”

Naturally, the mayor of tiny Buffalo, Iowa (25 miles west of the I-80 bridge), loves the idea.

“I believe it would be great to restore the natural prairie along the corridor, as well as to save demolition costs; establish a national park; and bring visitors to the Quad-Cities,” Mayor Sally Rodriguez said recently by e-mail.

She can’t wait to seize the irresistible promotional links between her small town and a Bison Bridge.

“Absolutely, our town would be partial to bisons and would welcome any marketing opportunities in the future for our great town and the Quad-Cities,” Rodriguez said.

But are buffalo and bison the same?

You know that iconic song of the American West, “Home on the Range”? It starts, “Oh, give me a home where the buffalo roam/Where the deer and the antelope play…”

A water buffalo, not the same as bison.

Well, the 19th-century author of the original poem (“My Western Home”), Brewster Higley, got a key detail wrong, according to the Smithsonian National Zoo. Buffalo never roamed the region, but bison still do. What’s the difference?

Though the terms are often used interchangeably, buffalo and bison are distinct animals. Old World “true” buffalo (Cape buffalo and water buffalo) are native to Africa and Asia. Bison are found in North America and Europe, according to the National Zoo.

Both bison and buffalo are in the bovidae family, but the two are not closely related.

How did the names get so mixed up? Historians believe that early European explorers are to blame, though the details are a bit murky. According to the National Park Service, it’s possible it stemmed from the French word “boeuf,” meaning beef, the National Zoo site says.

Others posit that bison hides resembled buff coats commonly worn by military men at the time, inspiring the name. Whatever the case, the misnomer stuck.

Bison have large humps at their shoulders and bigger heads than buffalo. They also have beards, as well as thick coats which they shed in the spring and early summer.

Bison in the U.S. once numbered about 40 million, but were nearly extinct by the start of the 20th century.

Bison have been an integral part of American history, a long preservation focus for the National Park Service (NPS), and officially the national mammal since 2016.

Bison are the largest land-dwelling mammal in North America, according to NPS. Males (2,000 lbs.) are larger than females (1,100 lbs.) and both are generally dark chocolate-brown in color, with long hair on their forelegs, head, and shoulders.

After four years of outreach to Congress and the White House, by the Wildlife Conservation Society, its partners the InterTribal Buffalo Council and National Bison Association and 60-plus Vote Bison Coalition members, the National Bison Legacy Act was signed on May 9, 2016, officially making the bison our national mammal. This historic event represented a true comeback story, embedded with history, culture, and conservation.

Less than 100 years ago, the American bison was teetering on the verge of extinction. By the beginning of the 20th century, the species’ numbers fell from herds of roughly 40 million at one time, to less than 1,000 individuals. The impact on Native Americans was devastating, according to the NPS.

In 1905, William Hornaday, Theodore Roosevelt, and others formed the American Bison Society to help save bison from extinction — the first national effort to save an American wildlife species.

The newest national park is New River Gorge in West Virginia, designated in December 2020.

The U.S. Department of Interior (DOI) – which oversees the Park Service — also helped reverse the bison’s fate. Beginning at Yellowstone National Park in 1872, the park protected its remaining two dozen bison. Today, through immense collaboration with diverse partners, DOI lands currently support 17 bison herds in 12 states, for a total of approximately 10,000 bison over 4.6 million acres of DOI and adjacent lands.

To honor such an iconic and resilient species, Congress passed the National Bison Legacy Act on April 28, 2016, making the bison a U.S. symbol of unity, resilience and healthy landscapes and communities. The Act recognizes the historical, cultural, and economic importance of bison.

“Although the recognition does not convey new protections for the bison, the Act recognizes the great conservation success story and importance of its comeback to Native Americans and rural communities alike,” according to the NPS. “This new and permanent designation conveys a vision of shared values of unity, resilience and healthy landscapes and communities. No other species is so iconic of American history and culture like the bison.”

Pregracke thinks bison are cool

In a recent interview, Pregracke said he hadn’t known bison was the national mammal, and hasn’t reached out yet to the National Park Trust – a nonprofit organization that works with NPS and has a “Buddy Bison” national education program.

“I haven’t really reached out to them yet, because I’m just trying to build local support, and then I’m going out from there,” Pregracke said. “I

The bison formally became the U.S. national mammal in 2016.

haven’t wanted to reach out to them yet because I don’t know what I need from them. I’m not at that point yet, but I plan on doing that.”

“For 20 years, I grew up right by that bridge, and I’ve just always liked bison and nobody was stopping,” he said of attracting visitors to that area. “As a teenager, I always thought it’d be really cool to have a small herd of bison there. Then when I heard they were gonna demolish the bridge and build a new one, I just sort of was like, put two and two together because I had already been doing the restoration, the prairie restoration and because of what the bridge looks like.

“You know how wide it is and non-obtrusive,” Pregracke said of converting it for pedestrian and wildlife use. “You don’t need it all for pedestrians. So how cool would that be? And then, if you look at the wildlife bridge in Utah, that was just, like, viral.”

He referred to a popular wildlife overpass completed in 2018 by the Utah Department of Transportation (over I-80, 1,231 miles west of our I-80), and a video from the state’s Division of Wildlife Resources shows dozens of animals using it to cross safely above six lanes of traffic. That overpass (in Parleys Canyon) is just 50 feet wide and 320 feet long, and its location was picked strategically based on animals’ migratory patterns, according to Smithsonian magazine. Experts originally anticipated that local wildlife could take years to get used to the new, animal-friendly infrastructure. But in 2018-2020, cameras placed along the bridge’s guardrail captured footage of not only the expected deer, moose and elk, but also predators and small mammals. The I-80 bridge across the Mississippi is 3,483 feet long.

“I just wanna see how many people are interested and then be able to use those numbers,” Pregracke said of gaining public support for Bison

Dave Herrell is president/CEO of Visit Quad Cities

Bridge. “That is definitely my main intention, to turn it into a national park. And I think this is a really good time to do it, if any time, and the fact that I’m not going to try to put something on that’s gonna cost them money.”

“I think it’s such a unique project. I don’t think it’s a huge land grab by any means,” he said. “I think it would be minimal maintenance to a certain degree. And if I’m able to bring a lot of money to the table, I don’t know why they wouldn’t, but I’m not them. But that’s Plan A. And if it takes a couple of different state parks, two different state parks, one in Iowa and Illinois, that’s fine.”

Dave Herrell, president/CEO of Visit Quad Cities, is a big supporter of the plan.

“When you get an idea like this and a proposal that is really creative and dare I’d say, like out there — I think communities that have big ideas are the communities that are the ones that I want to be a part of,” he said recently. “I think the fact that Chad and his team have brought this thing through on a lot of levels and they don’t have all the answers yet. And I think they’re working very diligently to get there.”

Herrell thinks the bridge project would really strengthen the Q-C’s brand identity as a great, innovative destination along the Mississippi.

“One of most important things is how we leverage and maximize the potential of our global asset — the Mississippi River — to do something that nobody else is doing,” he said.

“We need to think about, how are people connecting to it? What is that draw?” he asked. “It’s intertwined with our vision statement as an organization because we want to be recognized internationally as the riverfront destination,” Herrell said. “So if in order to do that, how are

A rendering of how a small herd of bison would share the old !-80 bridge with pedestrians and bicyclists.

you maximizing the potential of the Mississippi River? Well, if you can have ideas like this, that people have a connection to it and you can build a plan and a strategy to get there.”

“I am really I’m really proud of Chad and Living Lands and Waters, and the team and what they’ve assembled,” he said. “I think they’ve been very thoughtful along the way and I am honored that they brought us into the mix as well as other organizations like Quad Cities Chamber.”

Bison Bridge would be a major tourism asset, among many unique things to do in the Q-C, Herrell said.

“And by the way, no one else has something like this in the world and it’s ours — so that bragability factor that we’ve talked about a lot,” he said, noting their 2020 master plan shows just 48 percent of Q-C survey respondents said that they brag about living in the Quad-Cities.

“Every day we need to be thinking about how that 48% is growing and I guarantee you if we have things like the Bison Bridge, that we know come alive, that bragability number is going to go up,” Herrell said. “People want to be proud of the things in their town, tangible things they can touch and connect with in their community and something like that accomplishes that goal.”

“I think we’re on to something here. I know it’s going to be a lot of work,” he added. “I stand ready to do that with Chad and whoever, we can assist to tell that story. Whether that’s at the federal level, whether that’s in Springfield, or that’s in Des Moines.”

Why National Park Trust focuses on bison

The main image on the National Park Trust site “About Us” page is of a bison. Its mission is to “preserve parks today and create park stewards for tomorrow.”

“We acquire the missing pieces of our national parks, the privately owned land located within and adjacent to our national parks’ boundaries,” the site says. “We also bring thousands of kids from under-served communities to our parks; they are our future caretakers of

Students visited Washington, D.C. in 2017 with the Buddy Bison mascot.

these priceless resources.”

For over a decade, the group’s Buddy Bison School Program has provided fully funded park experiences for kids in under-served communities, including kids of color (pre-Covid, it served 20,000 students a year). Due to Covid, a new distance-learning education package was launched nationwide in Title I schools last fall.

“Covid-19 has created unprecedented challenges that impact students and families, especially those in under-served communities,” according to National Park Trust. “With 80% of Buddy Bison Program students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch, the federal indicator of low income, these students often do not have the resources at home to support online education or the complementary hands-on activities available to them that can offset hours of sedentary screen time each day.

“Working closely with teachers who are looking to provide fun, engaging educational activities that support their classroom curricula, the Buddy Bison Creative Learning Program will provide innovative programming that keeps students engaged with our parks and outdoor education while maintaining physical distancing and meeting new school safety policies.”

Buddy Bison is the NPT mascot because of its century-long importance to the nation, Ivan Levin, director of strategic partnerships, said recently.

“The bison is the national mammal of the United states, and has been an icon of the National Park Service and Department of Interior for a

The logo for the National Park Trust Buddy Bison program.

long time. It was chosen really for that reason – its size, its power, what it means to the country.”

Buddy Bison has “been part of our organization for a long time now,” Levin said. “He is our beloved mascot, who really represents programming.

“Underneath our Buddy Bison and youth programs, we really engage youth, underserved Title I schools across the country and engaging them in meaningful park experiences while also highlighting the wellness benefits of outdoor recreation, the importance of stewardship of our parks and really showing how parks can be used as classrooms.”

NPS wanted to engage students more, before Buddy Bison programs began, and “they were trying to understand why kids weren’t getting outdoors or weren’t connecting with our public lands,” Levin said. “That’s really when the Buddy Bison program came about, as a program that was meant to really get into schools and work with teachers and administrations and help them use parks as classrooms and specifically provide the resources and the experience for kids to actually go to a local park.”

Yellowstone National Park has the largest herd of bison, with about 4,800 animals. The smallest is a display/education herd of about 10 bison at Chickasaw National Recreation Area in Oklahoma.

Yellowstone says it’s the only place in the U.S. where bison have lived continuously since prehistoric times. Yellowstone bison are exceptional because they comprise the nation’s largest bison population on public land, according to www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/bison.htm.

A cuddly Buddy Bison enjoys the great outdoors.

Unlike most other herds, this population has thousands of individuals that are allowed to roam relatively freely over the expansive landscape of Yellowstone National Park and some nearby areas of Montana.

According to NPS, bison once numbered over 30 million, and ranging across North America, bison were hunted to near extinction, with only several hundred remaining by the 1870s. The 2020 DOI Bison Conservation Initiative is organized around five goals, including a commitment to conserve bison as healthy wildlife.

The National Park Trust is the only land trust with a comprehensive mission of preserving national parks through land protection and creating a pipeline of future park stewards by connecting kids to parks. Since 1983, the Trust has benefitted 48 national park sites across 28 states, one U.S. territory, and Washington, D.C.

“As a nonprofit organization, we have a lot more flexibility versus a government agency,” Levin said. “We work with the Park Service on their priorities. We help make a lot of those projects possible.”

There are more than 420-plus National Park Service sites – including 63 national parks. The newest one is New River Gorge National Park, designated this past December in southern West Virginia in the Appalachian Mountains.

Established in 1978 as a national river, the NPS-protected area stretches for 53 miles, and the park was officially named America’s 63rd national park, the U.S. government’s highest form of protection, during the Covid-19 pandemic as part of the federal relief bill.

Levin could not comment directly on the benefits of Bison Bridge, but said the most successful stories of establishing a national park start

Ivan Levin is director of strategic partnerships for the National Park Trust.

with a grassroots effort, which makes its way to Congress for designation.

“There are a couple ways that it can become part of the National Park Service, and it all starts from a grassroots effort,” he said. “You have to be of national cultural or historic significance. There always has to be some sort of significance.”

The newest national park, in West Virginia, had an advantage since it already was designated a national river, Levin said.

Units of the National Park System are designated by acts of Congress and/or through presidential proclamation. Congress directs the Department of the Interior through legislation to do studies of sites, to provide expert analysis about the resource qualities at the site and alternatives for protection, NPS spokesperson Cynthia Hernandez said recently.

The special resource and other study processes are designed to provide Congress with critical information used in the legislative process of

The Yellowstone National Park home page features a herd of bison.

designating a new unit, she said.

Those studies consider criteria for potential new units of the national park system, and such sites must:

- possess nationally significant resources,

- be a suitableaddition to the system,

- be a feasibleaddition to the system, and

- require direct NPS management or administration instead of alternative protection by other agencies or the private sector.

The White Sands National Park in New Mexico was designated in December 2019.

The previous most recent national park was designated in December 2019 — White Sands National Park in New Mexico, completely surrounded by the White Sands Missile Range. Previously considered a national monument since 1933, the park covers 145,762 acres in the Tularosa Basin, including the southern 41% of a 275-square-mile field of white sand dunes composed of gypsum crystals – the largest such field on Earth.

Do Iowa or Illinois have any national parks?

Neither Iowa nor Illinois technically have any national parks, but the two states have several NPS sites. They include:

· Effigy Mounds National Monument, Harpers Ferry, IA

Herbert Hoover’s birthplace and presidential museum in West Branch, Iowa, is a National Historic Site.

The mounds preserved here are considered sacred by many Americans, especially the Monument’s 20 culturally associated American Indian tribes.

- Herbert Hoover National Historic Site, West Branch, IA

Orphaned at age nine, Herbert Hoover (1873-1964) left West Branch never to live here again. In later years, he returned to his humble birthplace to celebrate his long career of public service, including serving as 31st U.S. President.

Lincoln (1809-1865) believed in the ideal that everyone in America should have the opportunity to improve their economic and social condition. Lincoln’s life was the embodiment of that idea. We know him as the 16th president, but he

A rendering of the pedestrian side of the proposed Bison Bridge.

was also a spouse, parent, and neighbor who experienced the same hopes, dreams, and challenges of life that are still experienced by many people today, according to NPS.

In a growing Chicago neighborhood, diverse people and stories intertwined. All were seeking opportunity. Some succeeded. Others were limited — by race, gender, or economic status. Their stories came together in Pullman, a planned industrial community famed for its urban design and architecture, according to NPS.

Illinois and Iowa also are included in two National Historic Trails – the Lewis & Clark (stretching 4,900 miles), across 16 states, and Mormon Pioneer (1,300 miles), across five states.

To learn more about National Park Service, visit nps.gov. For more on the National Park Trust, visit parktrust.org, and to support the Bison Bridge project, visit bisonbridge.org.